A Short History of Farm Loan Waivers and a Map of Farmers’ Pipe Dreams

|

Mannira.in Channel സബ്സ്ക്രൈബ് ചെയ്യൂ.

|

“If you give a man a fish he is hungry again in an hour. If you teach him to catch a fish you do him a good turn,” wrote Anne Isabella Thackeray Ritchie in her novel “Mrs. Dymond”, published in 1885. The 120 years old saying has coined new meanings and dimensions in the context of Indian states of the 2010s, which are raucous with explosions of exasperation, calls for arson and widespread protests of farmers in distress.

From Chhattisgarh farmers who crushed their tomato produce under truck wheels, sugarcane farmers in Uttar Pradesh sought permission to kill themselves, farmers in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana who chose to burn down their crops, farmers in Maharashtra who emptied milk vans on the road, to Trichy farmers who ate rat curry in front of the Trichy Collector’s office, point at the severity of the agrarian question of India, which is rooted in the growing inequality at a time of rapid growth of wealth and its uneven distribution.

Farmers along the length and breadth of India took it to the streets demanding hike in minimum selling prices and loan waiver packages in recent years. Be it a devastating attack of pink bollworm, a late-night demonetisation, drought, a medical exigency in the family, or stagnant prices, Indian farmers find themselves on the wrong side of everything. Ironically, prices paid by consumers for agricultural produces are much above the low prices earned by farmers. So, the agrarian crisis had to be dissected to filter its socio-political predicament, which is overcast by economic and populist rhetoric.

When it comes to populist measures to pacify raging farmers across the country, no other idiom is more popular among political folk than the farm loan waivers. Often, it is eulogized as the abracadabra to save Indian farmer from all the perils like low growth rate, poor earnings, large-scale internal migration, and disproportionately higher suicide rates! Since April 2017, ten states have given out farm loan waivers worth Rupees 1.9 trillion. Moreover, Congress had made national farm loan waiver an election promise ahead of the 2019 polls. Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh governments have declared packages for loan write-offs for small and medium farmers.

With waves of stringent criticism and complaints surface surrounding the implementation and scope of loan waivers, data shows that only a subset of farmers gets those benefits. Reports also suggest that nearly 60% of farm households do not benefit from loan waivers at the national level and it is as high as 85% in some states. Telangana farmers who received the much-lauded farm waiver package claimed that due to delays between instalments cleared by the government, the accrued interest of the pending loans cancelled out the benefits. Moreover, a large number of farmers, who benefited almost a 100% distress relief from outstanding crop loans under waiver packages, failed to repay their new loans again, an anomaly pushed them towards a recurring loop of indebtedness.

The inputs from the banking and agrarian sectors since the 1990s, a period from which the term farm loan waiver has become a populist tool, indicate that when a farmer’s loan is waived off, the chances of getting subsequent loans from the same bank is at danger because the bank authorities consider the farmer as a risky borrower with potential non-performing asset (NPA) threat. When the banking institutions step back, the only solace of farmers are the private money lenders. Unlike other industries, the plight of agricultural productivity is at the mercy of so many factors. A good or bad monsoon makes colossal impacts on production output and farmers’ income in a largely monsoon dependent country. The resulting income crunch makes marginal and small farmers disheartened and agitated and makes them vulnerable to the worse agrarian crisis in the country.

In order to tackle the low-income question, the Central Government announced a change in cost criteria for fixing minimum support prices (MSP). The MSP for Kharif 2018 and Rabi 2019 crops has been substantially raised. But, due to lack of infrastructure and procurement apparatus and exclusion of comprehensive costs (C2), which include costs like land rent, and inflationary effects on the economy, MSP has proved to be less beneficial for the farmers in distress. In most of the cases, the income is never enough to cover for the expenditure, and the farmers either abandoned their land to become migrant labourers or ended up in extreme measures like committing suicide. The historic evolution of rural indebtedness reveals the tragic story of regressive income redistribution, whose social, economic and political conditions have been accepting as unavoidable norms for centuries.

“Only a few know that agriculture in the small and irregular holdings of India is not a paying proposition. The villagers live a lifeless life. Their life is a process of slow starvation. They are burdened with debts,” wrote Gandhiji’s biographer D.G. Tendulkar in a 1953 article. In the pre-colonial period, farmers were primarily producing two crops, rice and wheat, and most of the villages were self-sufficient and sustainable to a certain extent with indigenous farming practices. After colonization, the British were keen to draw maximum profit from India’s agrarian sector and joined hands with regressive land ownership systems like the Zamindari system. The agricultural technologies remained primitive and reforms to upgrade them to ensure higher productivity had been neglected for a long period. Farmers were driven to mass producing cash crops instead of food crops, to cater to the demands of British industries.

The colonial rulers took sides with the feudal landlords to extract maximum profit before Indian agriculture, a cash cow for the British, fall on all fours. The periodic recurrences of famine coupled with the economic depression sparked peasant rebellions added fire to the freedom movement. The nation stepped into independence with incapacitated village economies whose self-reliance was destroyed and farmers had been raising arms for land reforms, higher wages of agricultural labourers, fixing higher prices, and rehabilitation of landless labourers on wastelands. The Desi governments’ reforms not only fared well in providing relief but aggravated farmers’ miseries.

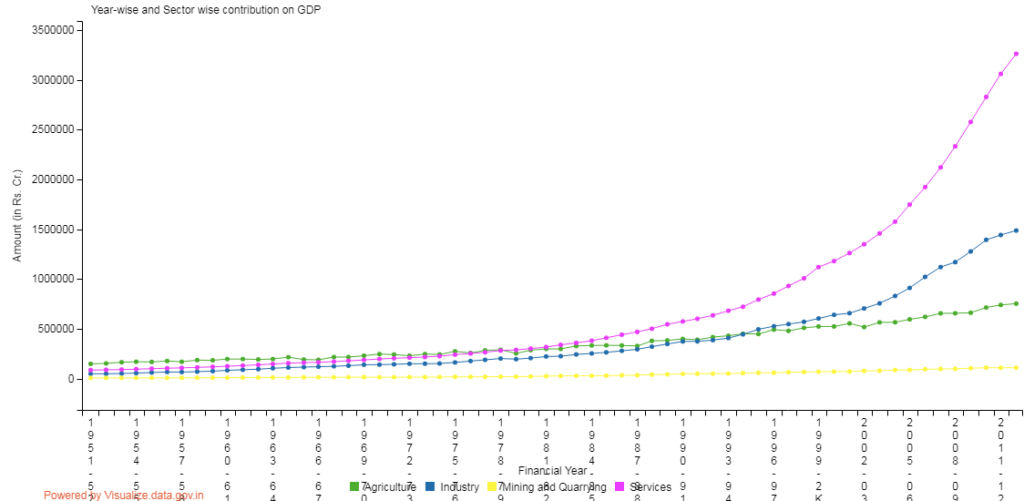

The first two decades after independence were the time of land reforms, irrigation development, and credit institutional expansion, whose objectives were not fully achieved. It was in the 1960s that India initiated a set of pragmatic new agricultural policies upon which the pillars of the Green Revolution were built. Even though agriculture plays an important role in the economy with over 58% of rural households depend on it for their livelihood, the share of agriculture and allied sectors like livestock, forestry and fishery in GDP had fallen between 15% to 20% after independence.

The wave of Green Revolution marked the second phase of Indian agrarian reform which brought in radical measures and controversial implications on distribution and exploitation of resources and yield per land, with the scale of agricultural development zeroed in on productivity only. Though the government tried to keep food security and farmers’ well-being as the two sides of the same coin with the formation of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) in 1964 and an Agricultural Prices Commission in 1965, the inequalities in wealth and land distribution wreaked a havoc on economic and social balance of the rural agrarian societies.

By mid-70s, the Price Support Policy of the government took a solid shape and MSPs were introduced to stabilise the agricultural system and encourage production. Ideally, MSPs rescued farmers from distress sales at severely low prices as they could sell it to the government when prices fall below the MSP, and the government could resell or channelize them to the public distribution system. Besides, the total Central and state subsidies for agriculture sector also increased over Rs. 2.2 trillion, constituting around 10% of agricultural GDP and 12% of average farm income.

But, after India’s joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, commercialisation of agriculture and market-oriented production became the norm and agricultural prices became highly volatile. With an avalanche of radical economic reforms, liberal import and export policy changes and international trade pacts, the small and marginal farmers of Indian villages mercilessly exposed to the whirlwind of global market and price wars. Derailed land reforms, income inequalities and wealth imbalances were widened and deepened. With the withdrawal of institutional support from the Government, agricultural sector and Indian farmers were left at the mercy of the market forces. Immunity enjoyed by many agricultural commodities from imports reverted, which in turn resulted in a steep fall in selling prices.

The 90s also opened doors to radical fiscal reforms, with crucial input subsidies were trimmed down. As a result, the small and marginal farmers had to spend high prices for seeds, fertilizers, insecticides, labour, and electricity. On the other hand, this hike in input costs was not compensated with a substantial increase in output prices and profit. The farmers fared badly in both good and bad monsoons because they found themselves on the losers’ side due to a fall in prices during a good harvest, whereas governments pulled down high prices with accumulated stocks or imports fearing public wrath during bad monsoon.

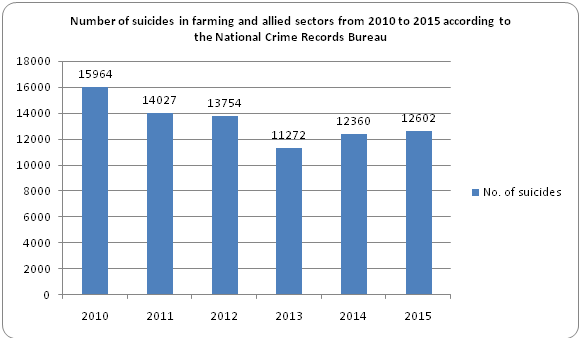

While a huge number of small and marginal farmers were deprived of MSP immunity, those who were lucky enough were suffered due to lack of proper infrastructure and procurement framework. By the end of the 90s, the malaise culminated into widespread agrarian uprisings with public capital formation for the agriculture sector and public expenditure on agricultural research dwindled. In the next decade, policies were designed according to the terms-of-trade and agriculture was played down by the industry and services sectors. The farmers were persuaded to use expensive, high yielding and genetically-engineered seeds, which escalated the cost of cultivation further and aggravated their indebtedness. Nationwide farmer suicide rates started to climb into alarming and disproportional figures.

The governments, eager to keep their pro-farmer, politically correct portfolio, created the “farmer suicide” category and designed compensation packages with rules to dying. The farm loan waivers became the most popular, both among the governments and the farmers, remedy for the disease. The first ever nation-wide farm loan waiver was announced then Prime Minister V. Singh in 1990, which cost the government Rs. 10,000 crore. The scheme disrupted rural credit framework with a proliferation of defaulters and the banks struggled for several years to recover from the blow. In 2008, P. Chidambaram, the Finance Minister under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, flagged off the farm loan waiver bandwagon of the 21st century with the Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme (ADWDRS), amounting to Rs. 52,000 crores.

In 2014, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana announced farm loan waivers of Rs 24,000 crores and Rs 17,000 crores, respectively. Tamil Nadu late Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa tried the same formula to cool down the wrath of farmers in the state in 2016 with the state coffers bore a burden of Rs 5,780 crores. Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh tested the farm loan waiver spell on the vexed small and marginal farmers in the state in 2017 with a package of Rs 9,500 crores. In the same year, Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah announced an ambitious scheme of Rs 8,165 crores. Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis couldn’t avert the populist appeal of loan waiver scheme and came up with a Rs 34,022 crore loan relief scheme.

Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan has announced a loan settlement scheme of Rs 6,000 crores on 2017. In the 2018 assembly polls in Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, Congress played the loan waiver cards with a contrivance to overthrow rivals who were reeling under the farmers’ wrath. While the election results were attributed to agrarian distress. Prominent economists like former Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan warned against the populist trend of using farm loan waivers as an election promise. In a report submitted to the Election Commission, Raghuram Rajan recommended impeding such sops, as it hinders investment in the farm sector and put holes on the finances of the states.

As loan waivers have been floating around as the populist and problematic solution for the agrarian crisis, Telangana put forward an off-centre move with the Rythu Bandhu scheme. Within a budget of Rs 12,000 Crores, the scheme, which is also known as the Agriculture Investment Support Scheme, dispersed an initial investment of Rs. 4,000 per acre per farmer for the purchase of inputs like seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, labour and other investments. The Telangana Government entrusted in this investment aid to accelerate agriculture productivity and farmers income and protect farmers from the debt loop. But, the scheme excludes tenant farmers whose number counts around 1.5 million. Inspired by the positive outcomes of the Rythu Bandhu scheme, the Odisha Government announced a similar income support scheme of Rs 5,000 crores in December 2018. The scheme, which includes landless rural farmers too, grants Rs. 10,000 to Rs 12,500 every year for investments in fisheries and animal husbandry.

While other parts of India were turbulent with farmer uprisings, Kerala executed its own model to solve the agrarian question. Kerala State Farmers’ Debt Relief Commission, which was formed in January 2007 under the counsel of economist Prabhat Patnaik, put forward a debt relief scheme based on negotiations between farmers and lenders. The commission sent a seven-member team constituted of farmers, legal experts, farm economists, political appointees and others to every village to interact with debt-ridden farmers. The team created complete debt portfolios of the farmers and fixed a customized loan settlement deal agreed upon by both the parties. Even though the project demanded dedicated and hardworking government officials and several days of sitting of the commission in villages, farmer suicides in the state dropped considerably within two years. The relief was provided to small or marginal farmers who borrowed from the cooperative sector, a major lender in rural Kerala. With the state machinery as the mediator, the initiative also helped the banks to solve the NPA crisis.

The facts and figures from last two decades clearly indicate that farm loan waivers are effectual solutions to address past distress, only as a one-time shot at the time of a financial emergency, and should not be used as a regular option. Moreover, it should be supplemented with a methodical future plan like investment support schemes of Telangana and Odisha, which are more equitable than loan waivers or price support schemes. The paradigm shift to income support schemes along with digitising and identifying every land-holding can solve the perils of corruption, inefficient procurement and storage and ineffective and distortionary crop incentives.

Instead of treating as a downbeat sector, agriculture should be remodelled as new India’s growth machine creating more jobs and wealth. Policymaking in agricultural, land, food inflation, exports, and energy sectors should prioritise improving farmers’ income by enhancing access to international markets and technology. An umbrella structural reform of strengthening the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, upgrading the crop insurance scheme, attracting more investment in agricultural research, adopting advanced farming and irrigation techniques, and a fixed cash subsidy system will not only ensure a decent standard of living for farmers but also a nation with state granaries full in all seasons.

Along with investment comes mechanization of agricultural process and better warehousing and transportation facilities. As the country is in a digital race to go cashless, taking technology to the farmers and eliminate the ever-widening digital divide is in the backseat. The profitability of the farmers can be enhanced by ensuring remunerative prices. When farming is upgraded as a profitable endeavour, the farmers’ capacity to bear losses due to droughts, natural calamities and crop diseases also increases. Timely and farsighted reforms of the APMC Act, Contract Farming, Essential Commodities Act and Future Trading and Land Lease Law fuels the above transformation. The agrarian sector employs women and men with a significant degree of gender discrimination. Female farmers with land holdings, who are small in percentage when compared to male farmers with land holdings, also being left out of mainstream agriculture activities like female farm labourers. As long as women are exploited as the cheap labour force, comprehensive agrarian reform exists only on papers.

It is ironical to argue that the proliferation of farm loan waivers damage an honest credit culture and credit discipline while millionaire businessmen fleeing the country as wilful defaulters, leaving behind a burden of millions on the banking system as unpaid loans. But, the financial challenges of loan waivers cannot be ignored, and demand immediate and long term remedies. Instead of luring farmers in distress with farm loan waivers for electoral benefits, they should be empowered to store, process and package their products so that every village in the country becomes self-reliant. Besides, lending institutions should operate with transparency and accountability guided by pro-farmer and rural-centric policies.

So, it is clear that the disease of rural indebtedness is deep-rooted in the past reforms and policy-making and embodies the centuries-old structural disquiet of Indian agriculture. Loan waivers act only as a quick-fix to ease farmers’ distress in the absence of coordinated and sustained reforms. Unless the real issues that push the farmers into debt crisis are identified and addressed, the loan waiver solution will only serve as a trump card in the hands of politicians and pose challenges like undermining public spending, price hikes, credit indiscipline and a moral hazard. This feat cannot be achieved without erasing the collective conscience about agriculture, which was once hailed as “God’s profession”, as an unprofitable and hopeless endeavour drawing small and marginal players towards tragic deaths or displacement.

Footnote: Union Agriculture Minister Radha Mohan Singh, while responding to a question by an MP in Parliament, revealed that the National Crime Records Bureau has not published figures of farmer suicides since 2016.

|

Mannira.in Channel സബ്സ്ക്രൈബ് ചെയ്യൂ.

|